The Nation’s Largest Collection Of Lighthouse Bloopers

When a specialized web site gets it all wrong about a place you know well…

August, 2017

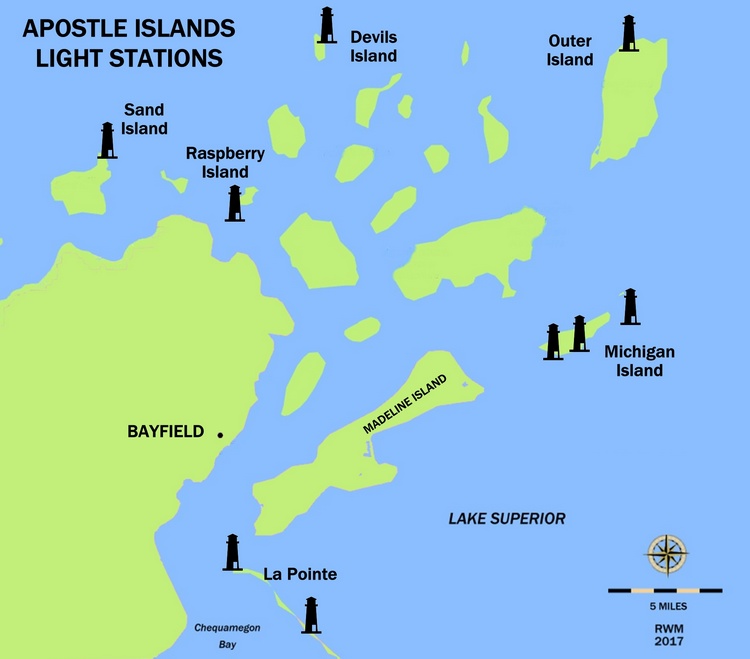

If you like lighthouses— and a lot of folks do— there’s no better place to visit than the Apostle Islands in Lake Superior. Six light stations on the archipelago off the northern tip of Wisconsin contain a total of nine historic towers and the ruins of a tenth, comprising what maritime historian F. Ross Holland called, “the largest and finest single collection of lighthouses in the country."

In my years as a ranger at the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore I grew accustomed to bumping up against bad information on the history of the lighthouses, sometimes in news items or travel articles, sometimes in the patter of kayak guides and tour boat captains. Though I considered myself pretty jaded by now, my eyes opened wide when I recently visited the popular Great Lakes maritime website, boatnerd.com, and came across a series of articles that makes a good claim for the title of “The largest collection of lighthouse misinformation in one place.”

Boatnerd is generally regarded as a reliable and comprehensive source for information on the ships that ply the Lakes, with vessel histories, photo galleries, news of arrivals and departures, and much more. However, there is also a section on “Lighthouses of the Great Lakes,” which, if its treatment of the Apostle Islands lights is an indication, should be taken with at least a year’s production from the salt mines beneath Lake Erie.

This series of articles, written by a gentleman named Dave Wobser, originally appeared in a magazine named Great Laker, whose URL now redirects to a publication called Great Lakes Seaway Review. They follow a rigid pattern with minimal deviation: ten cut-and-paste paragraphs of historical background and tourist information; then finally some details on the individual lighthouse. The articles are riddled with errors large and small, from dates off by a year or two, to some painful mutilation of Lake Superior 101.

I’ll examine the cookie-cutter intro sections first, using the Michigan Island Lighthouse page as an exemplar, then turn to the material about individual lighthouses in the pages that follow.

The Michigan Island Lights by Dave Wobser

Let’s start with the basics, as Mr. Wobser sees them:

A total of six light stations were established on the Apostle Islands between 1857 and 1891. They are Michigan Island (1857), La Pointe (1858), Raspberry Island (1863), Chequamegon Point (1868) Outer Island (1874), Sand Island (1881) and Devils Island (1891).

That makes seven.

Okay, math is hard. We get that. But here’s the thing: the Chequamegon Point beacon (which was not built in 1868—we’ll get to that in good time) was considered part of the La Pointe light station, and tended by the same keepers who looked after the “New La Pointe” tower just up the beach.

Now, to the early years:

The Apostle's (sic) originally received their name because early French explorers mapped only twelve islands.

Unlikely. It’s true that a French map of 1744 refers to the chain as Iles des 12 Apôtres – “Islands of the Twelve Apostles,” but by that point the cluster of 22 islands had been known to the French for more than 80 years, and it’s close to unthinkable that they were under the misapprehension at that late date of there being only a dozen. It is much more likely that the early French explorers, following a longtime tradition of bestowing religious names on geographic features, decided to lump the scattering of look-alike islands under one convenient group heading.

The French had established a major fur trading post in the islands from about 1660 to 1840.

Whoa, there! The trapper-explorers Radisson and des Groseillers did show up in the Chequamegon region in 1659, but their visit was brief, and after conflicts with government officials upon their return to Montréal, the pair turned their attention elsewhere. A handful of unlicensed traders followed their footsteps over the next few years, but it was not until 1693 that an actual “trading post" was constructed near the modern village of La Pointe on Madeline Island. This establishment was short-lived, however, perhaps a victim of its own success: in 1696, responding to a glut of furs flooding the market, King Louis XIV revoked its license, and the post was abandoned after only three years.

It was not until 1718 that stability was achieved with the opening of a second post on the island. This one continued operation until the outbreak of the French and Indian War, but in 1762, the French garrison fled the site and three years later the triumphant British destroyed the abandoned structure. While fur trade did continue as an important part of the local economy for some time to come, it did so under the control of British, and then American, authorities. So much for that “major French trading post from 1660 to 1840.”

Much of their trading was with the Chippewa (Ojibway) Indians who had lived in the area since the 1400’s.

The Chequamegon Bay region is considered the homeland of the Ojibway people, and the story of their arrival here is a subject of particular cultural sensitivity. William Warren, the son of a Yankee fur trader and an Ojibway mother, was the first to set the tribe’s traditional account down on paper. Writing around 1850, he recounted a tale of migration, beginning on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, then progressing westward in stages through the Great Lakes. Warren attempted to date the tribe’s arrival at Chequamegon by counting backwards by generations, and using a generous figure of 40 years per generation, came up with a date of 1492. (Ta-da!)

It would take several pages to discuss the complex and compelling history of the Ojibway and the other Native people who have occupied the area. Suffice it to say here that while Warren’s work is still considered a treasure-house of information, most modern scholars support the general outline of the traditional migration account, but move the chronology a century or more closer to the present.

Tourism and trips to summer homes of the wealthy had been established by steamers in the early 1800’s…

Hardly. The Chequamegon region was not even open to white settlers until the Treaty of La Pointe in 1854, much less posh summer homes. Steamers on Gitche Gumee were rare as hen's teeth before the 1855 opening of the Soo locks that allowed boats to bypass the rapids separating Lakes Superior and Huron. The first to be recorded on the big lake was the propeller Independence, laboriously hauled overland around the Sault Ste. Marie rapids in 1845. Tourism took off gradually once the locks made access practical for ships large enough to provide reasonably comfortable passage to Lake Superior ports, but the regional summer home tradition is generally considered to begin with the establishment of “Nebraska Row” on Madeline Island in the 1890s.

About the same time (as the opening of the locks), the towns of Bayfield, Washburn and Ashland were developing into shipping ports.

Washburn was not established until nearly thirty years later, in 1883.

In addition to these blatant errors, there are several misleading or exaggerated statements regarding the islands’ logging, quarrying, and commercial fishing industries; bad information on opportunities for camping; and some just plain carelessness: the National Lakeshore headquarters is on Washington Avenue, not Washington Street. But no sense beating a dead horse.

Next: The Michigan Island Lights

|